I can guarantee that in December 2017, news-savvy cisgender Canadians heard about a 23-year-old woman named Lindsay Shepherd. But they may not have heard about a 27-year-old woman named Alloura Wells.

Wells was a young transgender woman who went missing in Toronto last July. Her body was identified on November 30, following months of indifference and silence from law enforcement and community organizations. Wells was funny, smart, and well-liked, and her community continues to be deeply affected by her untimely loss.

Lindsay Shepherd made headlines as the Wilfrid Laurier TA taken to task by her superiors for showing students a clip of Jordan Peterson discussing gender-neutral pronouns. The columnists who reported on Shepherd did so with fervour, but also with care. She was not just some graduate student — she was “engaged and lively,” an “avid reader,” “open-minded and conscientious,” “keeping with the true spirit of academic freedom,” and a “vegetarian, pro-choice, universal health-care supporting environmentalist and ardent supporter of free speech.” Shepherd was, and is, presented as a complex human being.

Wells, on the other hand, was rarely described as anything more than a body. There were very few stories that spoke of her as a person. For the most part, all we learned about her was her gender and her circumstances, usually focusing only the sensational details of her struggles.

It has been exhausting to watch the Canadian media make a mess of covering the transgender community. Our experiences have been largely reduced to a pronoun circus, with transgender subjects treated like interchangeable props to support cisgender players. The absence of transgender voices in the media on this issue, including those of trans students and faculty at Laurier and on other campuses, has been startling. Cisgender media have rendered this episode as yet another incident where trans people are invoked in the abstract rather than having their stories heard.

Transgender people are continually reduced only to “snowflakes” on campuses, while the actual issues that materially affect us — poverty, racism, discrimination, housing, etc. — get erased from the narrative right up until the moment that one of our deaths makes the news. And even in those cases, it is rarely recognized as a wakeup call.

When a trans person dies, it makes headlines for a short while. Then, everyone forgets about it. They forget that 20% of trans people in Ontario have experienced transphobic physical violence, and that 70% of transgender youth in Canada have been victims of sexual harassment [pdf]. They forget that, in Toronto, researchers believe that over 25% of homeless youth are LGBTQ, yet one in three trans people is rejected from a homeless shelter based on their gender. They forget that trans women in Canada face a “constant risk” of violence. They forget that we often encounter difficulty and discrimination when trying to access healthcare, especially if we are Black, Indigenous, or other people of colour [pdf].

People may become aware of these realities if the media reports on a trans person’s murder or disappearance. But this context rarely informs other coverage of the issues facing our community.

Too often, cisgender writers and audiences fail to engage with transgender people and our pressing concerns. There are few (if any) trans people who are hired to write on subjects that directly concern us; there is little recognition of the roles played by trans people in the stories created around us; and there is no responsible coverage of the transgender community beyond our role as hypotheticals. In the eyes and words of cisgender media, trans people are sites of deviance and debate. Beyond that, they’ll hear nothing we have to say.

There are very few transgender people currently employed in newsrooms across the country, and this lack of perspective results in frequent cases of misrepresentation, and a lack of engagement with transgender sources.

Here’s an example: In the spring of 2017, Pride organizers in several Canadian cities opted to exclude uniformed police officers and floats from their parades, following a 2016 demonstration by Black Lives Matter in Toronto.

The bans on uniformed police were celebrated by many members of the transgender community, given the disproportionate violence that LGBTQ people, especially people of colour, experience at the hands of police. Almost immediately, cisgender editors across Canada strongly condemned the decisions, arguing in impassioned defence of the police.

Those same cisgender voices are noticeably silent on the Toronto Police Service’s horrific mismanagement of Alloura Wells’ disappearance — ineptitude that now appears to have extended to the investigations of other missing persons within the queer community. In fact, over the course of the four months in 2017 that Toronto police spent not looking into the disappearance of Wells, coverage of transgender issues by cisgender writers focused almost exclusively on pronouns and campuses.

There is perhaps no greater indication of the dearth of transgender people in Canadian newsrooms than the seemingly unending parade of terribly repetitive pieces on pronouns. The topic is front and centre when it comes to “trans issues” in Canadian media.

Cisgender people write about this pronoun debate as the be-all and end-all of transgender issues, largely speaking only to other cisgender people, and thus missing out on the whole story. Meanwhile, on Twitter, Shepherd has been dismissing claims of transphobia on campus and mocking trans students and their allies — you know, the usual purview of open-minded advocates for academic freedom.

It’s astonishing that cisgender writers have simultaneously reported this subject to death and left it completely unstudied. Markers like names and pronouns affect our access to bureaucracies and official records. This means that our interactions with service providers, government offices, and state institutions are disproportionately fraught with opportunities for rejection, obstruction, and discrimination. As you can imagine, these sort of experiences (as minor as they may seem) can feel especially taxing for students, given that they are usually between 17 and 22 years old, lacking in genuine community and capital, and are often thrown into situations where they are attempting to access services without assistance for the first time, while juggling everything else in their lives. (And in the rare cases that these incidents are covered in mainstream Canadian media, cisgender writers often replicate the same transphobia.)

None of this is exactly news, though it has managed to largely escape the coverage of trans issues in Canadian media. Even when cisgender readers and writers are confronted with the consequences of transphobia in the form of sensationalized stories, most voices in the media manage to reduce our experiences to quibbles over pronouns in the same week.

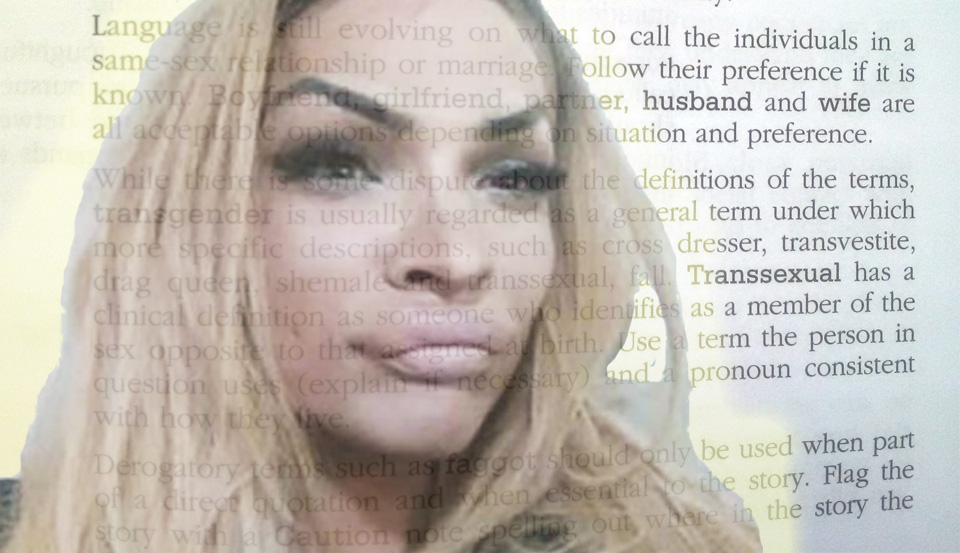

As a whole, cisgender writers and editors have never been particularly good at covering the transgender community. We are often misrepresented in order to fit narratives that are more palatable to cisgender audiences. Editorial standards can sometimes inadvertently endanger us. Until very recently, The Canadian Press style guide relied upon outdated and offensive tropes about transgender women, such as conflating them with drag queens and using insulting terms like “shemale.” (The newest edition, just published in September, finally replaced this with more nuanced and sensitive guidance.) Taken together, these practices contribute to harmful public perceptions of trans people and our stories. We are regularly represented only in the abstract, and rarely given the opportunity to share our own perspectives.

When it came to covering the transgender community, 2017 was a year of missed opportunities. I wish we could actually have a genuine conversation about the issues facing transgender Canadians, but I don’t believe that can happen without adequate representation.

Alex V Green is a writer based in Toronto who writes about the politics of community and identity. You can connect with Alex on Twitter @degendering.

Top image of Alloura Wells alongside outdated language from the 17th edition of The Canadian Press Stylebook (published in 2013).