Student journalists are readying for a fight after Ontario’s Ministry of Training, Colleges, and Universities announced on Thursday it will allow postsecondary students to opt out of “non-essential” fees, including levies for student publications.

Minister Merrilee Fullerton said levies for athletics, health, and career services, among other programs, will remain mandatory. Beyond that, it’s up to each university to decide which fees are “essential.”

That means student publications, already operating on shoestring budgets, could see their resources cut as early as September.

Jacob Dubé, the editor-in-chief (EIC) of Ryerson University’s The Eyeopener, thinks that declaring student media and other campus resources “non-essential” says a lot about the government’s priorities.

“They don’t care what the services are, they don’t care how it helps,” says Dubé. “If you save an extra $5, they’ve done their jobs.”

Every student paper’s financial model varies, but all rely heavily on fees. Those vary in size, but are generally under $10 annually for a full-time student.

But since students who opt out out that fee could still enjoy the product, it might not matter how cheap it is.

“If they wanted to, they could read the paper without having to pay for it,” says Anchal Sharma, EIC of the University of Ottawa’s The Fulcrum. “And the thinking will be ‘no harm, no foul.’”

Funding for some papers is guaranteed through referenda. But the government’s announcement would apparently overturn those.

“Everything that is funded here is funded because students chose to support it,” says Dubé. “If you can overturn it with an opt-out, that overturns the whole process … They say they’re treating students like adults, but this just removes the agency from us.”

Even if students are willing to pay, editors worry the opt-out model would make publications vulnerable to campaigns from fringe groups on campus, who could push to defund papers for their own reasons.

“I don’t think that would be the case in the current climate,” says Jack Denton, EIC of The Varsity, the University of Toronto’s tri-campus paper. “But we know that anti-media sentiment is catchy and could be very dangerous.”

Student papers are already constantly under threat of being shut down. Last year, the University of Manitoba’s student paper, The Manitoban, was almost defunded by its student union after publishing a critical editorial. In 1994, the University of British Columbia’s student paper, The Ubyssey, was shut down by its student union, in part for its scathing coverage.

“The fact that that could shutter a very old, important institutional like The Varsity is scary,” says Denton.

Student journalists are fighting back by challenging the notion that journalism is “non-essential,” especially after Premier Doug Ford’s demand for campuses to enact free-speech policies.

“It’s pretty ironic that the Ford government, which seems to be really big about free speech on campus, is calling student journalism non-essential,” says Emma McPhee, president-elect of the Canadian University Press.

“News is essential. It’s as essential as clean air and public education to a democracy.”

Asked if the government considers campus press to be “essential,” a spokesperson for the ministry writes that services that “Support institutions in providing critical campus-wide services and activities which are integral” would be considered essential, but did not say whether campus press falls under that category.

The government has deferred the responsibility for determining what is “essential” to individual institutions. Spokespeople for the University of Toronto and Ryerson both said it was too soon to say which fees they’ll require students to pay.

If push comes to shove, student papers are ready to make their case.

“They’ll have to answer for it,” says Dubé. “They’ll have to tell us to our faces that we’re not necessary.”

The government’s announcement is bad for universities. It could be even worse for Canadian media.

“A lot of our writers aren’t journalism students; they found their passion for journalism through the community at The Fulcrum,” says Sharma.

For students, campus papers effectively serve as alternatives to costly journalism schools — accessible doors into a notoriously closed industry. The Eyeopener, for example, was founded because only journalism students were allowed to write for the pre-existing paper.

Sharma says losing them would “change the face of Canadian media as a whole” — especially since student papers often lead the pack in challenging long-standing biases in Canadian journalism.

“Student media tends to be the place where there’s a lot more hope for where media is going in Canada,” says McPhee. “Canadian media is very white and still quite male. Having a more accessible way into journalism is something that matters.”

And whereas journalism programs cost money, and internships are often unpaid, student papers actually compensate editors for their work.

Rosa Saba, a freelance reporter who has written for The Globe and Mail and Ottawa Business Journal, studied at Carleton University’s journalism school — but credits The Charlatan, the campus paper, with igniting her career.

“It showed me that there were multiple ways to be successful in journalism — that you didn’t have to follow that one path,” says Saba. “It looked really good on my resumé, and it paid my rent, and that’s pretty much everything I needed.”

Jacob Lorinc, a reporter at Moncton’s Times & Transcript, says he “got his degree” at The Varsity, where he was editor-in-chief.

“You learn a million different things working as the editor of a paper that you really don’t get a chance to learn anywhere else in any other capacity,” says Lorinc.

https://twitter.com/robyndoolittle/status/1085950335670054912

Student journalism is journalism. Student newspapers are a critical part of campus life. Doug Ford doesn't understand post-secondary education or campus life and his policies will leave each worse off. He ought to reverse course immediately. https://t.co/76SCG7Uc6s

— David Moscrop (@David_Moscrop) January 18, 2019

The ministry’s press release says the new fee model will “ensure transparency, choice and ease of decision-making.”

But it might cut funds for the only institutions that actually fight for transparency on campus.

Last summer, The Fulcrum and La Rotonde, the University of Ottawa’s French-language paper, broke news that their student union was under investigation for fraud. But funding for those papers comes from the student union’s general fee — which is now considered non-essential by the ministry.

Sharma worries that students will withdraw their fees from the union because of the allegations of corruption against it — inadvertently undermining the institutions that hold it accountable.

“I feel pretty confident that a lot of students will choose to opt out of the student union levy,” says Sharma. “And when they do that, we’re done.”

If student papers aren’t covering those institutions, it’s unlikely anyone will.

“Other media outlets rely on student media to find those stories that matter to students, and then they bring them to national attention,” says Denton. “Without us, you’re going to cut those stories off at the knees.”

So how essential is student journalism?

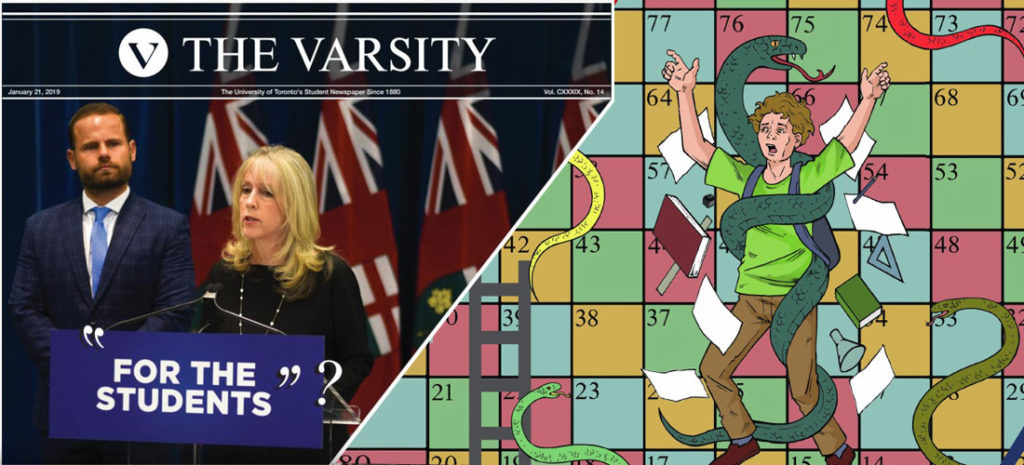

At the press conference where the fee changes were announced, Minister Fullerton stood in front of a sign reading “For the Students.”

But only one reporter asked her if any students had actually been consulted on the changes: The Varsity’s Andy Takagi. Her response suggested she hadn’t.

After I asked about who was consulted for the provincial plan to make cuts to tuition, Minister Fullerton couldn't name a single student group or university her office consulted about this plan despite standing in front of a sign that read: "For the Students" #onpoli #ONpse pic.twitter.com/h38DQg5FoR

— Andy Takagi (@andy_takagi) January 17, 2019

The point proved itself. Sometimes, student journalists are the only ones asking the questions that matter.

Zak Vescera is the web news editor at The Ubyssey.

Top image assembled from the January 21st covers of The Varsity and La Rotonde.