At a quarter past noon on November 5, 2013, Toronto Mayor Rob Ford casually admitted — after months of denying it — that, yes, he had smoked crack cocaine. This had most likely occurred, he quickly explained, in one his drunken stupors.

Nearly three hours later, as reporters stood crushed against the glass wall of Ford’s office, tensely awaiting entry to what promised to be one hell of a press conference, Vice dropped a bombshell: “Rob Ford’s Office Hired a Hacker to Destroy the Crack Tape.”

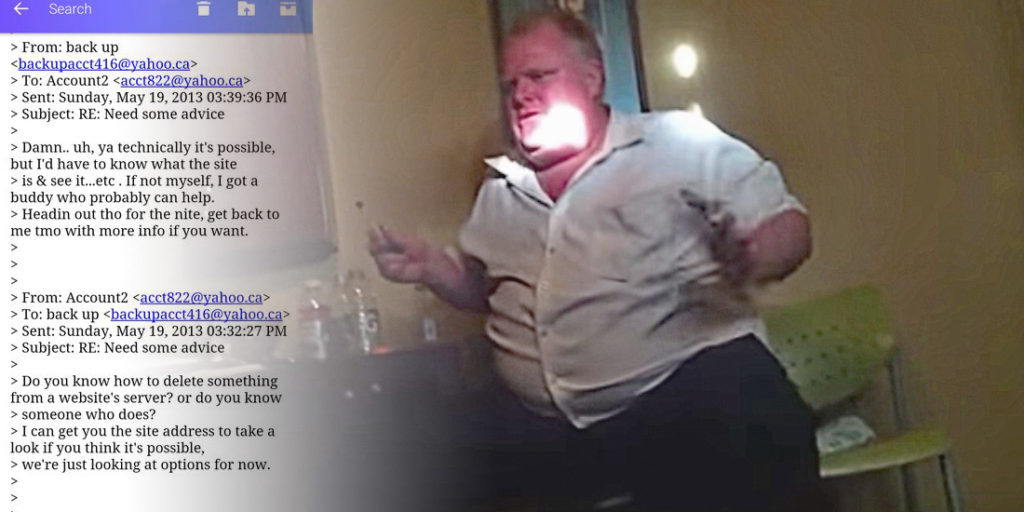

The story was bursting with jaw-dropping details concerning alleged efforts by Ford’s communications director, Amin Massoudi, to pay a “hacker” to break into a password-protected server in order to find and delete a video of the mayor smoking crack. Loaded with quotes from what it described as correspondence between Massoudi and the hacker, the report, by Vice Canada’s then-managing editor Patrick McGuire, offered an apparently unprecedented view into a political office scrambling to contain a crisis.

“The closets are being emptied of skeletons all over it seems,” read one passage from an email attributed to Massoudi. “I’ve never seen the bros [Rob and councillor Doug Ford] this pissed off before.”

A hush fell over the reporters gathered outside the mayor’s office. Everyone appeared to be skimming the story at once, another astonishing branch of the Ford saga seeming to sprout before our eyes. It was exactly as plausible as everything that had come before it and everything that would come after.

Except that it was false. Just completely bogus. And Vice had paid $5,000 in cash for the privilege of running it.

On August 11, 2016, some months after Ford passed away from cancer, the crack video finally became public. A criminal charge had just been withdrawn against an associate of his, and a publication ban no longer applied to the evidence.

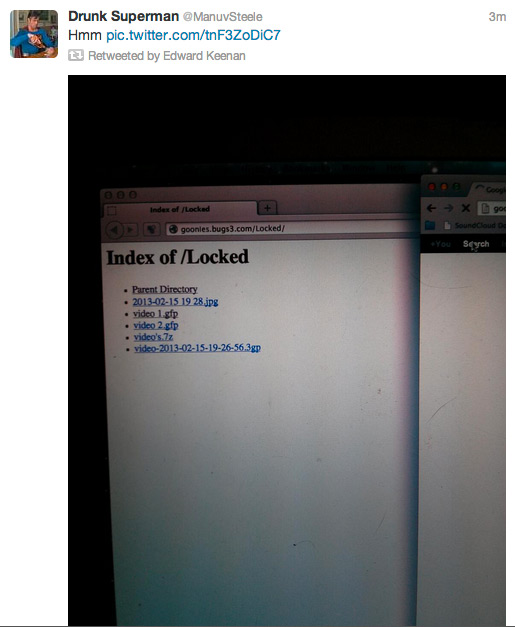

Late that night, a person who went by “Drunk Superman” on Twitter suddenly offered an admission.

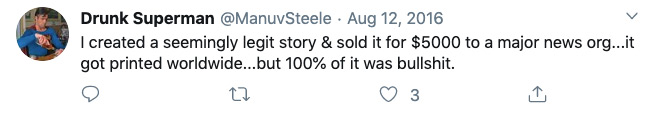

“I created a seemingly legit story & sold it for $5000 to a major news org…it got printed worldwide…but 100% of it was bullshit,” he tweeted.

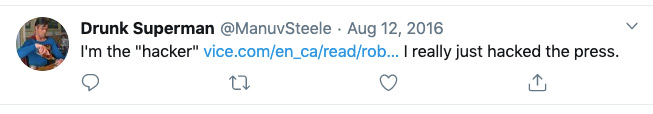

“I’m the ‘hacker,’” he said, offering a link to the Vice story. “I really just hacked the press.”

Drunk Superman, with the handle @ManuvSteele, was a minor character in the Fordian Twittersphere, a playful troll sympathetic to the mayor. Within that realm, he wasn’t especially obscure.

But his confession somehow escaped broader notice, even as he immediately stepped away from Twitter, letting those eight tweets linger at the top of his timeline for the next three and a half years. (They only came down a couple months ago.)

I was a staff writer for NOW Magazine at the time, and reached out for an interview. To my surprise, Drunk Superman happily agreed, on the condition I not publish his real name. We decided I could call him “ManuvSteele,” and “Steele” on subsequent reference.

A couple weeks later, we met on the patio at Ronnie’s, a quintessential hipster haunt in Kensington Market, where I bought him whatever IPA they had on tap. (They didn’t carry his first choice, Amsterdam Boneshaker.) He was a scruffy white guy in his early 30s, or maybe late 20s. The only words I scribbled down concerning his appearance were “Tupac hat.”

Over the course of three hours, he told me everything: about pulling off the deception, how he came to profit from it, and why he now wanted to come clean.

But there was a fundamental quandary: If he lied to media then, how could I know he wasn’t lying now? Why, I asked him, should I trust this wasn’t just another con, within a con, like in a David Mamet movie?

“I’m not asking for any money,” he said. “I’m asking for a couple pints, maybe.”

And also, he said he felt guilty.

But not with respect to Vice, or to McGuire, the reporter he duped. Rather, Steele felt bad for the staff in the mayor’s office.

“I want to clear everyone’s name out of this, because I faked the whole fucking thing,” he said. “But there was never a proper time for me to actually disclose it.”

The story had falsely implicated Massoudi and former chief of staff Mark Towhey in the supposed (and likely illegal) hacking scheme. It also included a suggestion that Massoudi himself had been looking to acquire drugs (“a ball”).

Neither Massoudi nor Towhey responded to Vice’s requests for comment prior to publication, but both later put out statements strongly denying the story’s claims.

“Allegations made about me in Vice are patently false in their entirety,” Towhey tweeted. “I am completely unaware of any facts that support their story.”

Allegations made about me in Vice are patently false in their entirety. I am completely unaware of any facts that support their story.

— Mark Towhey (@towhey) November 6, 2013

“The entirety of the story is false, and everything referenced therein has been fabricated,” read part of a three-paragraph missive Massoudi sent to Vice and at least two outlets that were looking to report on its claims. “It is telling that the story neither quotes any named sources nor provides any independent corroboration of the alleged hacker’s information. The story does not meet even the most basic of journalistic standards.”

The denials were forceful but not altogether out of character for the staff of an office that routinely dismissed genuinely accurate media reporting in similar terms.

Massoudi, now principal secretary to Ontario Premier Doug Ford (and who had been Doug’s executive assistant at City Hall when the supposed communications with the “hacker” began), did not respond to my requests for comment.

And Towhey, who later wrote a book about his time in the mayor’s office and recently left a job as editor-in-chief of Sun News, tells me that he has “no particular interest in revisiting this old, false story.”

But as for why he didn’t respond when Vice first reached out for comment, Towhey offers: “It’s hard to win an argument with a liar.”

Steele fully acknowledges he lied.

“Yeah, 100%, I did lie to Vice about it,” he told me.

At first, I was deeply wary. But over time, my doubts about his meta-story have been gradually resolved. I’ve spoken to a number of people who’ve independently corroborated key elements of his account, including that Vice paid him $5,000 in cash. He also showed me evidence in person, such as messages within the Twitter app on his phone, that — while not impossible to falsify — would be much more difficult to manufacture than the bits and pieces he gave Vice. And Vice had already quietly appended an update to their story, five months after its original publication, stating that a forensic investigation by the City of Toronto disproved the veracity of one particular email that had ostensibly been sent from Massoudi’s official City Hall account.

I never got around to writing about any of this in 2016; it wasn’t especially timely, and I had others things to deal with. But with Canadaland’s recently-wrapped Cool Mules series offering a longform look at how Vice’s culture and attitude left it vulnerable to exploitation, I’ve found an excuse to tie up some loose ends.

“I’m not a fuckin’ hacker”

“They’re supposed to be like the standard in journalism, especially now, like they’re one of the best investigative reporting bureaus in the world,” Steele told me in 2016. “They’re the ones who had gone to North Korea and they’d gone to all these weapons markets and done their research there.”

He seemed to have held Vice in genuinely high regard, and was almost dismayed by the ease with which he was able to put one over on them.

“I think they were more unethical than I was, because they didn’t do the proper research. They were willing to pay for a story that could be verified as fake.”

ManuvSteele considers himself a libertarian but not a “hardcore” one. Asked in 2016 if he considered himself a Ford supporter, he said, “I like a lot of his policies. I like shit disturbers. I am one myself.”

The germ of the hacker story began in June 2013, in shit-talking Twitter DMs with an acquaintance. In an act of pure chest-puffing, Steele took to claiming he had some sort of inside track on the Ford tape.

While Gawker’s effort to crowdsource $200,000 towards its purchase had been successful, the outlet’s source was now telling them it was “gone.”

A defining characteristic of this period in Toronto history is that it felt like any given thing could possibly be true and any given event might conceivably unfold; like a first-time viewing of 2001: A Space Odyssey, the saga seemed to have no limits as to what might happen next.

Steele found himself in the Financial District, where an intermediary handed him two envelopes, each containing 25 $100 bills

In that context, the idea that a random Twitter bruiser might have access to a website hosting the video, if only he could crack the password, would hardly have been out of the question. And so the conversation in Steele’s DMs gradually turned toward getting a piece of the cash.

He reached out to Gawker, stringing them along, off and on, for months. He claimed Ford’s office recruited him to find the video because they’d been impressed by his discovery, during the 2010 municipal election, that an unflattering edit to Ford’s Wikipedia page had come from an IP address traceable to the parent company of the Toronto Star.

Gawker, however, was only interested in paying for the video itself; the encrypted, unwatchable RAR file Steele claimed to have found on the server didn’t exactly warrant a bounty.

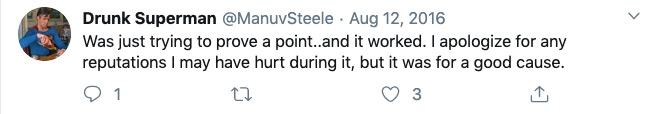

But both in 2016 and in more recent communications with me, Steele has been firm in his assertion that his interest in the money was secondary. Frustrated by what he saw as the media’s reliance on unnamed (or as he put it, “anonymous or unknown”) sources in reports on the mayor, he wanted to see if he could plant a fake story and pull the rug out after.

The cash, he said, “was just the cherry on top.”

While things stalled with Gawker, Steele’s Twitter acquaintance — who remained under the impression that he was telling the truth — suggested they approach Vice, where he knew the managing editor, McGuire. The pitch would be: all of the information, including server login info and encrypted video files, for $5,000.

As a matter of principle, news organizations generally refuse to pay for information, specifically because it creates a market for false information. They will, however, sometimes pay for photos and videos. (The Star later shelled out $5,000 for the Rob Ford “Hulk Hogan” video, and the Globe put down $10,000 for images from the second crack tape.)

What exactly Vice agreed to buy isn’t clear. Steele says that all of his direct communications with the outlet were through a long-gone Hushmail account, as well as some phone calls he conducted from an anonymized number. He also maintains that they never knew his real identity.

“I just wanted to see if I could plant something,” he said. “And then all of a sudden, I’m being offered money for it. So I actually took some time to set it up properly, because I know Vice is really well-known for their investigative reporting.”

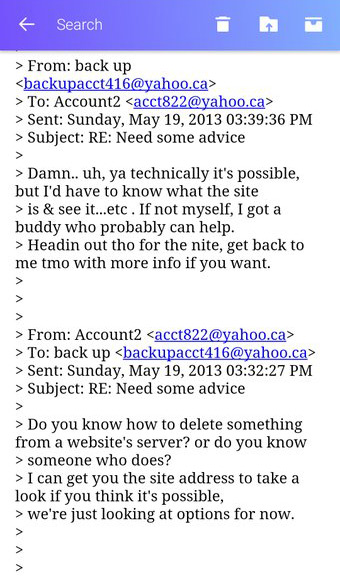

Doing it “properly” mostly involved creating some Yahoo accounts to forge correspondence between himself and Massoudi.

“I just put it together as much as I could,” he said. “Sat there for like three to four hours in total, typing emails back and forth to myself.”

Because he couldn’t easily backdate all the emails — just the ones threaded in replies — he made sure the messages made reference to specific recent events, and then took screenshots with the email headers conveniently out of frame.

He also set up a free server at goonies.bugs3.com, its name a reference to the Dixon Goonies gang that had just been raided by police and whose members were rumoured to be in possession of the video. He loaded to the server a pair of hefty files — his friend’s skateboard videos, impenetrably encrypted.

“I’m not a hacker, I’m not, like, an IT whiz or anything like that,” he told me. “But it was basically anything anyone with a little bit of computer knowledge could have really done, if they had the ambition to.”

Steele soon found himself at a square in the Financial District, where an intermediary handed him two envelopes, each containing 25 $100 bills.

He went straight to the Eaton Centre, he told me, and put a deposit on the forthcoming PS4.

Vice didn’t end up running the story that summer. The absence of the email headers proved a sticking point for McGuire’s superiors in New York, and Steele’s excuse (that he had shut down the account before he approached Vice) left something to be desired.

“The unnamed source claims to have deleted the very evidence he or she is now trying to pawn over the Internet,” Massoudi noted in his public statement. “Any alleged evidence is clearly fabricated.”

But when, on Halloween, Toronto’s police chief confirmed his force had recovered the video — reconstructed from a deleted file on a computer seized in the raid of the Dixon gang — Vice apparently considered its qualms to have been sufficiently addressed.

“VICE exhaustively compared the emails allegedly from Massoudi with public notes and comments Massoudi left on his Facebook profile,” McGuire wrote in the story. “Both were rife with grammatical errors, poor spelling, and had a similar tendency to overuse elipses [sic].”

Vice had also tried to confirm the authenticity of the one message supposedly sent from Massoudi’s official City email account, but discovered it was outside the scope of access-to-information laws. That confirmation, the story said, “is the only thing that would prove the transcript’s legitimacy beyond a shadow of a doubt. (VICE believes the transcript to be real.)”

They published a few hours after Ford admitted to smoking crack.

Soon, @ManuvSteele was dining out on Twitter, strongly hinting he’d been the story’s source. Among the nuggets he shared was an image that could conceivably have been a still from the crack video but was in fact an old, accidental photo of his thumb.

— Drunk Superman (@ManuvSteele) November 7, 2013

Rather than pulling the rug out, Steele was doubling down. There was, after all, no longer any doubt that Ford had smoked crack and that police possessed a gang-connected video of him doing so. The reveal, he reasoned, wouldn’t have quite the same punch.

When a reporter from one of the national networks reached out, Steele saw a chance to repeat the grift, asking for $10,000 for material he hadn’t shared with Vice, including, he implied, the video itself. The network agreed, booked a room at a Howard Johnson, and prepared to shoot an interview with him in silhouette. But when it became evident that the only videos Steele could show them depicted his friends skateboarding, the news team packed up their cameras, took their money, and left.

Gawker followed up around the same time.

“We spent like a grand on supercomputer processing time, trying to crack the password on an encrypted file he said he got off some skating web site, in the hopes it was the tape,” John Cook, the site’s editor at the time, and the first person to report on the crack video, tells me in a message. “Never went with his story because I had no reason to trust him, but the idea that we had an encrypted version of the video was too much to not try something…”

Run This Town, the recent film featuring Damian Lewis as a freakishly plasticized facsimile of Ford, is not a good movie. It displays little sincere interest in, or curiosity about, politics or journalism, instead treating the Ford saga as a convenient vehicle to explore tenuously connected themes of millennial dissatisfaction.

I regret to inform you that this is an official promotional still from the Damian Lewis–as–Rob Ford movie: pic.twitter.com/8lCg82nDwd

— Jonathan Goldsbie (@goldsbie) February 28, 2020

But there is one thing it gets almost right, possibly by accident. (Spoilers.)

The film’s protagonist is a young journalist named Bram Shriver, who one day lucks into a tip about a video of Ford smoking crack. Far from being a male incarnation of Robyn Doolittle, the actual newspaper reporter who got the real-life tip, Shriver is just barely competent. He wants so badly to play investigative reporter, to have a scoop, to contribute breaking news to the Rob Ford civic universe, that he lets himself be driven by confirmation bias and ego. Eventually, he persuades his editor to hand him $10,000 in cash to purchase the video from the seller.

When Shriver returns to his office with a thumb drive, he discovers the video on it will not in fact play. (The movie is fuzzy on whether he’s been conned or the file is simply corrupted.) The film concludes with him scooped, humiliated, and fired.

“Everyone was just so hungry for any little story that it was like, ‘Okay, I’m giving you the information. You guys could check it out. But no, you guys are so hungry for any information, to be the first ones to get the new exclusive,’” Steele said.

Patrick McGuire, who reported the story, was later promoted to overseeing all content produced by Vice in Canada, including for its Viceland TV channel. He’s now Red Bull’s global head of music, based in London, UK.

He didn’t respond to my requests for comment.

Vice, meanwhile, acknowledged, but did not respond to my questions. I wanted to know about any policies they had around paying for information (and how those may have evolved over time), and any steps they might take in light of the news that their source had admitted to a hoax.

“I could probably go and do this again with someone else,” Steele boasted to me in 2016. “It wasn’t that hard, and I’m no hacker.

“I mean, I’m not a fuckin’ hacker. I just know a little bit more than the average squirrel.”

As of this moment, the piece remains on Vice’s website, unmodified since the one small update in 2014.