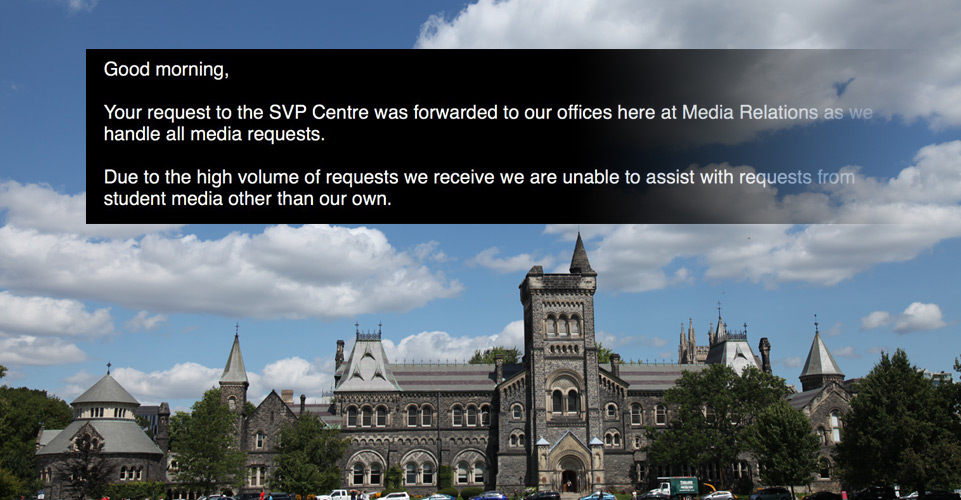

The University of Toronto does not grant media requests to student media other than its own. I found this out by accident, after sending an email as part of a story looking into sexual-violence education at big universities across Canada.

Four days after sending out the interview request, I received word back from the University of Toronto. The email from their media relations team attributed the policy to “the high volume of requests” they receive, so as a reporter for The Ubyssey, the University of British Columbia’s student newspaper, I was denied.

Hey, @UofT — just a reminder that all student media is media, and has the capacity to hold you accountable! pic.twitter.com/MyDvTWlzA9

— Samantha McCabe (@sam_mccabage) August 21, 2018

The Canadian Association of Journalists released a statement shortly afterward calling U of T’s actions “unacceptable,” writing, “The University of Toronto and other post-secondary institutions must recognize that student journalists are journalists.” As reported by The Varsity, U of T’s student newspaper, the university has thus far upheld its decision. Elizabeth Church, interim director of U of T Media Relations and formerly of The Globe and Mail, said that they are “considering how we can revise our practice to address some of the issues that are being raised.”

Almost every student journalist seems to have at least one similar, frustrated anecdote. Speaking to both past and present student media revealed that they are frequently dismissed and disregarded — often on the basis of not being “real” journalists.

“One of the main lines that people use to discredit us is that we’re student journalists … without even considering the quality of the story itself,” says Emma McPhee, who did two stints as editor-in-chief of the University of New Brunswick’s The Brunswickan and is the vice-president of the Canadian University Press, a newswire service owned by student newspapers across Canada. “And I have seen that hurt the confidence [of] some of my reporters and editors.”

Olivia Robinson, who is pursuing a master’s of journalism at Carleton University, says she was denied a second interview with a public library in Ottawa because it came too close on the heels of her previous school assignment. Melanie Woods, previously editor-in-chief of the University of Calgary’s The Gauntlet, recalls getting printouts of their stories handed back to them with highlights and edits made by the university’s media relations team. The Gauntlet never made the changes, unless they concerned factual errors (they rarely did, says Woods).

Others describe being told by their universities to wait for comment on a breaking issue, only to see stories from bigger outlets go up first with the comment included. One graduate of a journalism program in Calgary says she and her student newspaper colleagues were frequently denied media passes to events put on by their own school.

The difference seems especially pronounced to those that have “graduated” into the world of bigger newsrooms and name-brand recognition.

“In terms of how you’re treated as opposed to ‘real’ news outlets, it’s pretty night and day. And I actually got experience with that: as soon as I landed an internship at the [National Post], I was able to attach that big name to requests,” says Jack Hauen, former coordinating editor of The Ubyssey, now with the Toronto Star. “Even the exact same people I talked to at UBC would get back to me within the day, as opposed to within the week.”

For Hauen, it was a few days’ difference between the school year and the summer internship.

“It’s like you go from an annoyance to a relationship to be cultivated,” he says.

Sierra Bein, former editor-in-chief of The Eyeopener, Ryerson’s independent student newspaper, recently wrapped up a summer internship with the National Post. As soon as she started working for the Post, sources would scramble to get back to her, something she had never experienced before.

“It feels like just the way that I’m being perceived,” she says. “Because my level of skill hadn’t changed within a few hours, but here I am being treated very differently depending on what email I’m using.”

This isn’t always limited to interactions with people working in public relations. In an industry where networking and personal connections can often mean the difference between a steady job and unemployment, students say it’s difficult not to take the hit hard.

“It’s that lack of solidarity that really bugs me,” says Hauen, “because that feeling of not feeling like a real journalist is not exclusively cultivated by interactions with media relations people — sometimes, unfortunately, it’s also cultivated by the people who you look up to. And that’s pretty tragic.” He says his own mentorship with a Ubyssey alum was invaluable to him, especially during a time when he was trying to build up both experience and self-confidence.

“So much of journalism, like anything, comes down to feeling like you’re allowed to be in the field or you should be in the field. And I can only imagine that that feeling is multiplied for anyone who’s not a cis white dude and can’t even see anyone who looks like them in prominent journalism positions in the first place,” says Hauen.

Audrey Carleton, who worked in a variety of roles at The McGill Tribune for four years and has just finished up an internship with The Globe and Mail, points out that some pursue their student newspaper as an alternative to graduate school, because it’s cheaper.

“It just makes people feel like … just because they don’t go to j-school that they’re not going to ever really be part of this industry. That was something that I always feared, and still fear now.”

"It's unacceptable for our post-secondary institutions to ignore media requests from student journalists," says CAJ vice prez, Evan Balgord, about @UofT's recent refusal of a media request from @UbysseyNews. Full statement: https://t.co/geFaUjBV2x 1/4 pic.twitter.com/0T1CIvFXFS

— Canadian Association of Journalists (@caj) August 24, 2018

Some of the discrepancies in treatment may be legitimate: student journalists are still learning the trade, and campus newspapers are thought of as the ideal place to make mistakes. Any editor at a student newspaper will tell you that there are a lot of volunteers who just stick around to write an article or two and hang out with friends. Other students take the task incredibly seriously, especially if they are using their university beat to create clippings that will propel them into their eventual careers. Some are undergraduates, and some are in graduate school. The label of “student journalist” may not encompass these differences.

Shelley Divnich Haggert, who teaches journalism in Windsor, Ontario, has seen journalism students from a variety of backgrounds and disciplines who are pursuing it for different reasons.

“Especially now, when we are talking so much about the importance of journalism and unbiased coverage … it’s very important that they get all the facts, and yet in their effort to get all the facts, they run into closed doors? And so I think that’s discouraging,” she says.

She also acknowledged that just like any industry professional, student journalists need checks and balances, such as ethical training and close scrutiny from their editors.

“Fourth-year journalism students are doing pretty much the same kind of work that a journalist in his or her first year at the Toronto Star, or CTV, or CBC would be doing. There’s really not much difference,” says Aneurin Bosley, an assistant professor at Carleton University’s School of Journalism and Communication. “Obviously there have been some pretty big stories … in particular, in the last couple of years, that have been broken by student journalists.”

In Bosley’s experience, the work of students at j-schools often goes through the same vetting process as in newsrooms.

Woods, the former Gauntlet editor, acknowledges that some student journalism doesn’t hold up to standards. But some, even compared to the work of major media outlets, shines through.

“I disagree with the idea that you’re allowed to set up norms and practices and rules that define who is a journalist,” says Woods. “I think that’s something mainstream media does to protect itself. Anybody can be a journalist. The difference is moving away from the individual and acknowledging good journalism. A student journalist is a student journalist, and they can produce good journalism and bad journalism.”

This nuance, she says, is key — understanding what makes a well-reported, engaging, ethical story.

How do we define who is a journalist, and who isn’t? Who makes the rules, and who deserves to be treated as legitimate?

“I’m not really sure where the balance should be,” says McPhee. “But I do think that student journalists should be treated with respect. As much respect as you’d give any journalist. Just as you should give anyone respect, regardless of their position in society.”