As the strike at the Chronicle Herald moves into its second year — and with the possibility of a bad faith bargaining complaint looming — the union representing striking newsroom staff and the paper’s management are preparing to take another stab at resolving the conflict.

They’re bargaining again after months without official negotiations. During that time the union attempted to drive the situation forward by filing an unfair labour practices complaint to Nova Scotia’s Labour Board — a complaint Herald managment deemed groundless. That hearing had been scheduled to start Jan. 23, exactly a year after the dispute began, but was postponed this week while bargaining resumed.

Even as both sides express cautious optimism about negotiations, the labour hearing is an acrimonious cloud on the horizon, and an additional source of uncertainty for those on strike.

“Putting your life on hold for a year isn’t easy,” said Ingrid Bulmer, Herald photographer and president of the Halifax Typographical Union (HTU). The HTU represents 55 striking editorial staff at the Herald. “You can’t necessarily plan for the future because you’re thinking ‘we might be going back to the table next week.’ ”

But for Stephen Forest, a striking page editor with 30 years experience at the Herald, his shifts on the picket line have had an unexpected upside: he’s spent more time with the colleagues he used to work with in the newsroom than ever before. On a mild and rainy day in January, he and a handful of other strikers are talking sports, waving to the cars that honk in support as they pass by.

“It’s important that people that drive up and down [the street] see us here each day,” Forest said. “In a way we have become a fixture. We’ve quite familiar with the neighbors who walk their dogs by here; we know the dogs by name.”

Yet after 12 months on the picket line, it can be hard to stay positive.

“We’re standing here in the rain, and people are in jeopardy of losing their homes. They’re chewing through their life savings to keep afloat through this strike,” Forest said. “It’s pretty discouraging when the CEO of the company drives by the picket line, looks right at you and smiles. There’s just something wrong about that.”

Rather than thinking about the number of times Herald CEO Mark Lever has passed them on his way into the building, Forest focuses on numbers of a different sort: the quantity of coffees and cold drinks dropped off by members of the public; the 60 pairs of thermal socks the strikers received from another union; the supply of handwarmers that will get them through another winter on the picket line, if it comes to that.

. @cupenovascotia brings the heat. @NanMcFadgen dropped boxes of handwarmers to @HTU_official today. Many thanks. #solidarity #CHstrike pic.twitter.com/MysbIPVr7j

— Stephen Forest (@ForestStephen) January 17, 2017

What they’ve stopped counting — even as a glimmer of light appears at the end of the tunnel — is the days before they reach a resolution with Herald management, according to Bulmer.

“We’ve stopped having those discussions, because when we first went out, we…said it can’t be any more than four months, [then] it can’t be any more than six months…basically we’ve just stopped wondering, and you take it each day at a time.”

In the year since the strike started, the union has lost six members to other outlets or different jobs; they’ve also made concessions to management, including a five percent wage cut, and an increase in working hours. Even before the strike began roughly half of the striking employees were put on a layoff list, including Forest, meaning they’ll lose their jobs when the strike ends. But so far, these concessions have yet to result in a deal.

Yet the Herald’s approach to the strike has evolved. In the strike’s early days, the Herald withheld bylines. Attribution has now returned to some stories, and the company has continued to produce newspapers.

But the HTU said Herald management has refused to budge on the fundamental details of the contract offer that sparked the strike, and has continued to put forward contracts that the union would certainly refuse,

“We believe that they’ve been offering proposals that we simply cannot sign and they knew it,” Bulmer said.

Meanwhile, the union has continued its own news coverage, through a website it has dubbed the Local Xpress. The publication started as an additional bargaining tactic, but has evolved into an outlet in its own right.

Monty Mosher, a striking sportswriter for the Herald, began covering local sports for the Xpress, which he calls a “lifeboat,” after the strike began. After all, if he didn’t, there were few people who would.

“There are a million places where you can get coverage of the Toronto Maple Leafs,” he said. “But there aren’t a lot of places where you can get coverage of the Mount Allison [University] Mounties and the Dalhousie Tigers, and I believe [those] people have great stories to tell.”

And thus enters the bind facing the strikers: Nova Scotia’s paper of record has been plagued with errors since the strike. These mistakes have ranged from uncaught typos in wire copy, such as one that put Fredericton, N.B. in Prince Edward Island, to a story that numbered the homeless population of Nova Scotia at 200,000, in a province with fewer than a million people. But as vindicating as those errors have been, they’re also frustrating.

“For people who have worked their entire careers to try and build up the paper… [and] took extreme pride in reporting for the Chronicle Herald…to see this thing fall in upon itself so quickly is disheartening,” Forest said. He noted there seems to be little by way of mentorship for the replacement workers currently reporting for the Herald, many of whom are less experienced than the staff they’re replacing.

https://twitter.com/zwoodford/status/821774853174870016

The most well-publicized example of the Herald’s falling in on itself came in the summer, with a controversial article on Syrian students at a local elementary school. In that story, a pseudonymous source named “Missy” alleged bullying by Syrian children, including an incident in which a “refugee boy” choked a girl with a chain while yelling ”Muslims rule the world.” The story was roundly criticized and subsequently retracted.

Bulmer said while the possibility that the paper could be making itself irrelevant is worrisome, the union has committed to building up readership once a resolution to the strike is reached.

If the upcoming round of bargaining does not succeed, the unfair labour practices complaint could move the process forward. That complaint would address the HTU’s accusation that by prolonging the strike, the company is trying to dismantle the union.

“If the company’s intention is to freeze us out, we’re hoping that the bad faith bargaining complaint will bring that to light,” Bulmer said.

Ian Scott, the Herald’s chief operating officer, told the CBC removing the union had “never even crossed [their] minds, frankly.”

If the Nova Scotia Labour board determines that either party is not working towards a resolution of the dispute, it can order a change in behavior under the province’s Trade Union Act.

When asked for a comment on the unfair labour practices hearing, Scott forwarded a statement in which he wrote, “[Managment] said from the outset there was no basis for a complaint,” and that the proposed contract that sparked the strike is necessary to help the company deal with declining subscriptions and shrinking revenue.

The Herald has referred to the previous collective agreement with newsroom staff as “gold-plated” and “unsustainable.” In its challenge to the bad faith bargaining complaint, management also said the company’s proposed contract was an effort to create a “modern newsroom:” increasing efficiencies by reclassifying reporters as “multimedia journalists” — so that they would also be expected to take photos — and moving production jobs to a non-union hub, similar to ones used by Postmedia and TorStar.

Scott has also said that the paper is trying to reduce costs by shrinking the number of people working in the newsroom, which he acknowledges would diminish the union.

Current Herald employees and replacement workers contacted for this article declined to comment on the record about the strike, some citing concerns about their positions, but sources at the paper say morale in the newsroom is low.

But Bulmer said that if they union were to go back to work, they’d want more than just a contract that everyone can agree on — they’d also want recognition that they weren’t replaceable.

“We would like to see the company to realize that, number one, they devalued their journalists, thinking that it was going to be easy to bring in strikebreakers,” said Bulmer.

The Chronicle Herald was founded 143 years ago today, Jan. 14, 1874 as The Morning Herald. May she see many more yrs w/ new vigour & purpose pic.twitter.com/kfE29IuzRD

— HTU (@HTU_official) January 15, 2017

Whether the strike ends in the upcoming weeks, or lurches toward a conclusion with the bad faith bargaining hearing in February, it’ll be a long period of discord and worry to come back from. And as the union marks the one-year anniversary of the strike with rallies around Nova Scotia, they’ll be hoping that the public take note of the anniversary too.

“One of the things that’s been difficult is that sometimes you feel a little bit isolated…it’s important to feel that people care in some contexts. They can agree with us, they can disagree with us, as long as they remember that we’re still here,” said Monty Mosher.

“After a year, it’s easy to be forgotten.”

***

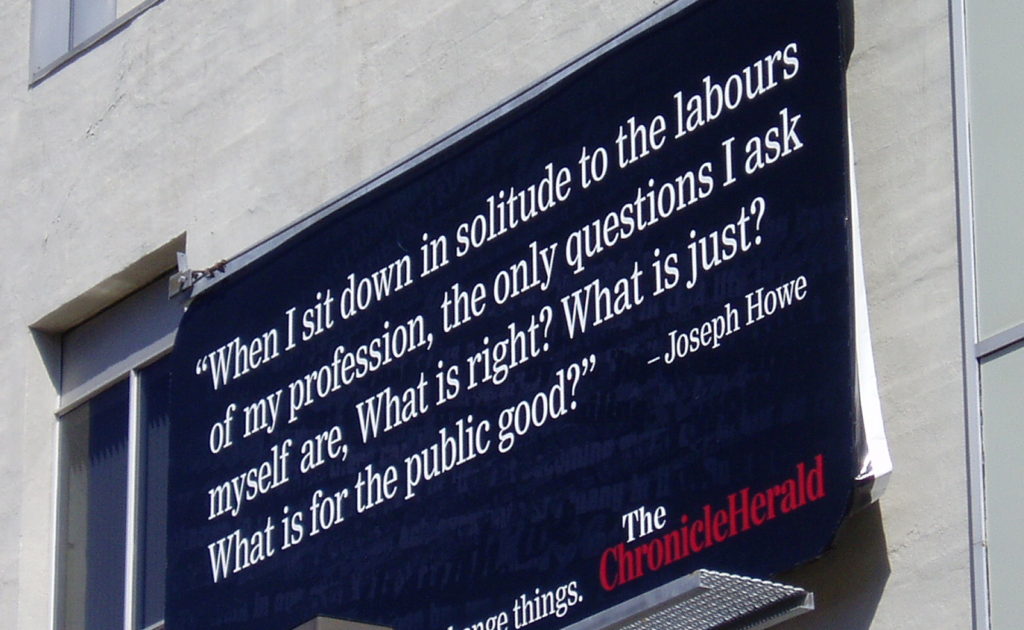

PHOTO CREDIT: RicLaf/flickr